Last Updated on February 9, 2026 by Brian Beck

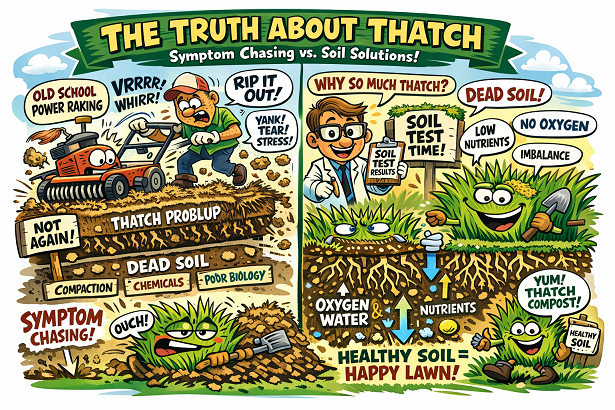

If you’ve ever peeled back the green canopy of your lawn and found a spongy, brown layer that feels like an old welcome mat, you’ve met thatch.

Thatch is the intermediate layer that forms between the green grass blades and the actual soil. It’s made up of slowly decomposing plant material—stems, runners (stolons), roots, crowns—mixed with a little soil. A small amount can be normal. But when that layer thickens, it becomes a barrier between your lawn and the resources it needs to thrive.

Why too much thatch is a problem

When thatch builds up beyond a reasonable thickness, it starts acting like insulation in the worst way:

-

Water struggles to infiltrate evenly → runoff, dry spots, or shallow rooting

-

Oxygen exchange gets restricted → roots and microbes underperform

-

Nutrients get “stuck” above the root zone → the plant stays dependent on quick fixes

-

Disease and pests find a cozy home → humidity + decaying material = trouble

-

Your lawn becomes “puffy” and unstable → poor footing, scalping risk, uneven mowing

Here’s the key idea: thatch buildup isn’t the disease—it’s the symptom.

What actually causes thatch?

The popular myth is that thatch is just “too many clippings.” In reality, clippings are mostly water and soft tissue—they break down quickly when the soil is alive.

Thatch builds when production outpaces decomposition.

Common drivers of that imbalance

-

Dead or biologically weak soil (the big one)

-

Overuse of synthetic nitrogen (fast top growth, more stems/runners, less balance)

-

Fungicides, insecticides, and harsh chemical programs that suppress decomposers

-

Compaction / tight clay that limits oxygen and slows microbial activity

-

Shallow, frequent watering that keeps roots and biology stuck near the surface

-

Low organic matter / low humus (no buffer, no “engine room” for biology)

-

Grass varieties with aggressive stolons/rhizomes (can contribute, but still comes back to decomposition)

When the soil can’t “digest” organic matter efficiently, that material accumulates. The lawn becomes a factory with no cleanup crew.

The traditional response: power raking (and why it’s so stressful)

The classic recommendation is to power rake (or dethatch). And yes—it can remove a chunk of that layer.

But here’s the problem:

-

It’s physically traumatic to the lawn (tears crowns, stolons, and living tissue)

-

It’s timing-dependent—often pushed when the lawn is dry/dormant or in a narrow window

-

It frequently leaves the lawn open to weeds and stress

-

Most importantly: it’s symptom chasing

Power raking is like scraping plaque off your teeth without changing your diet. You’ll feel progress… right up until the underlying conditions rebuild the same issue.

The root cause: a soil that isn’t functioning

Thatch is often a billboard that says:

“The soil biology is not cycling organic material back into plant-available nutrition fast enough.”

When the soil system is functioning, thatch becomes food. It gets broken down and returned as usable resources—nutrients, carbon compounds, and improved structure. That process also opens the soil so essential resources like oxygen and hydrogen (water) can move into the root zone more effectively.

So instead of asking, “How do I remove this?” the better question is:

“Why isn’t my soil digesting what the plant is producing?”

The real solution: identify what’s misfiring with a soil test

If you want thatch to stop coming back, you need to stop guessing.

A good soil test helps you pinpoint the constraints that slow decomposition and restrict root function—things like:

-

pH issues that create nutrient lockout

-

calcium/magnesium imbalance that tightens soil and limits airflow

-

low organic matter/humus (no sponge, no buffer, no biology engine)

-

fertility patterns that push growth without supporting decomposition

Once you know what’s off, you can correct the soil so it can process thatch back into the system instead of storing it as a problem.

What “fixing it” looks like in a living-lawn program

When you address soil function, the early wins often show up before the lawn “looks different”:

-

better infiltration

-

less runoff

-

more consistent moisture in the root zone

-

improved nutrient movement

-

deeper rooting and less stress cycling

Then the visible stuff catches up: density improves, weeds fade, and the lawn becomes less dependent on constant inputs.

And if you want to accelerate the whole process? Combine soil correction with consistent mowing (robotic mowing is king here)—because frequent, clean cuts and tiny clippings support a steadier carbon cycle instead of boom-and-bust growth.

Bottom line

Power raking removes thatch. Soil health prevents it.

If thatch is showing up, don’t just rip it out and hope. Use it as a diagnostic signal. Get a soil test, identify what’s misfiring, and rebuild the system so your lawn can recycle its own material—turning “waste” back into nutrition and opening the soil so water, oxygen, and resources can actually reach the roots.

If you want help interpreting a soil test and building a correction plan that actually solves it, that’s exactly what we do.